Introduction

We got to move

We live in a complex world that seems to become even more complex due to man-made and natural, large-scale disruptions such as globalization, climate change and robotization. There are no easy answers to handle this complexity. The root causes are often not well understood, let alone that it is easy to find ways to make progress when it is not clear in what direction people should be heading. These large-scale disruptions are beyond the control of ordinary citizens, yet they do interfere with the mundane challenges found in local communities, such as independent living for elderly people, loneliness, and local climate change countermeasures; all of which are complex challenges in their own right. We have no other option but to adapt to new circumstances. And although the challenges we face may be global, we can face them by starting out locally with relatively small initiatives, which can then evolve into larger movements. In retrospect, not every initiative and/or direction taken will prove to be right. But alleged or real mistakes are also something to learn from. The point is, we got to move.

Organizing solidarity

Because no one has a monopoly on wisdom and we cannot assume that a single person can steer us away from the cliffs, we have to find ways to address challenges collectively. While we must change the world together, often not all parties involved will be truly on board. This results in situations in which we try to find a solution for you, but not with you. Meaning that, despite good intentions, decisions are made based on advice coming from one or only a few stakeholders. Not all relevant perspectives are taken into consideration and solutions are not widely supported. We believe that in order to find solutions that will last, a process of social innovation is needed in which all stakeholders are involved and given a voice.

No one can stand on their own - in the sense that we are always in need of each other. This dependency results in a moral obligation for care responsibilities, or at least it implies that we have this obligation. Therefore, in a social innovation process, solidarity is essential. But how do we organize solidarity and true involvement of all parties involved? In a society in which we have become increasingly individualistic, this is not an easy thing to do. How do we organize a process involving all citizens, businesses and institutions, that lets us move into a direction that is arguably desirable and culturally feasible? This question is difficult to answer, because of its many-sided facets. A first observation is that we have to address solidarity by focusing on relations between us and the different sorts of ties that bind us all (i.e., who are we and what do we do). This requires a deep understanding of different relations at work at various places and the beliefs and the concerns of all people who are faced with specific challenges. We must realize that we are interconnected: the relationships between us humans are what matters because someone or something cannot be seen on their own.

A second observation that follows, is that all parties concerned must collaborate, thereby recognizing that each individual has their own role to play, and that each role brings along its own responsibilities. The roles and responsibilities individuals have, are not always in concord. Talking things through will often lead to understanding, but not necessarily to agreement. In practice, people will clash. We should, therefore, engage in a fruitful dialogue, see how solidarities are enacted and avoid a premature closure of debate in all circumstances. It is a process permanently in the making. However, in order to deal with the wicked problems we are faced with, we got to move together.

Creating room for sustainable changes

But even when we try to change situations together, there is no guarantee that changes will last. In current society scarcity in time, money, capacity or other means, often forces us to look for quick and efficient solutions. In a short period of time, we must analyze a problem, form our opinion, choose a direction and take action. And once we have voiced our opinion or chosen a direction, it does not seem desirable to reconsider either one of them. But how do we know that the chosen direction is the right one? For sustainable changes, every party involved has to change, in order to support a new direction taken. But change does not come overnight. We must take time to truly understand a problematic situation at stake. We must explicate and share how different stakeholders involved view this situation. Only then, new solution directions can arise that will last over time.

People have a subjective view on the world, which they express in their narratives. They have many beliefs and assumptions that determine the position from which they observe the world. Most people are not aware of their beliefs and assumptions. As a result, their worldviews might be limited and as a consequence their ability to find directions for movement might be limited. It is important to broaden people’s worldviews by critically reflecting on the worldviews of others as well as their own. If people gain insight into beliefs of others, their worldview may tilt, and their own assumptions may change and broaden. This asks for room for reconsideration of opinions, of worldviews, of directions. Only when we together start to explicate our worldviews and the situation at stake, can we start to look for what binds us, what is our shared meaning within a certain situation and which direction we together believe is right. Only then, can we move together in the right, and therefore sustainable, direction.

Framework

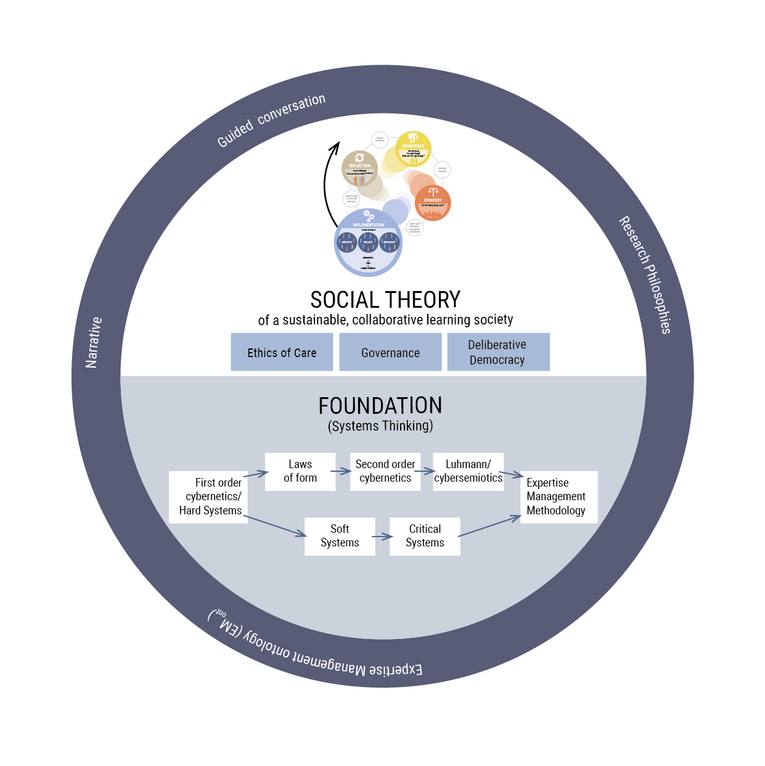

This book introduces a social theory of a sustainable, collaborative society (or Social Theory, ST, for short). ST offers a framework for realizing sustainable changes that are widely supported in society. ST can be seen as a theoretical framework to bring about change with lasting impact. As such, it provides processes, methods, tools and insights in order to answer the following question:

If we constantly got to move and react to changing circumstances, how can we do this together and in such a way that it will be meaningful and thus worth the effort?

The term theory might come across as a collection of ideas not rooted in reality, devised by a researcher stationed in an ivory tower. But as Kurt Lewin famously stated: “There is nothing as practical as a good theory.” ST has an extensive theoretical foundation. But first and foremost, it is the result of years of practical experience in the field of social innovation. Working side by side and being in a constant dialogue with stakeholders involved in social innovation projects, interpreting and reinterpreting experiences, enriching these with theoretical insights, resulted in a wider understanding of wicked problems and how to come to sustainable solutions.

As said before, ST offers a framework. It is not an ideology, proclaiming to have the answer to everything or offering the only truth. Nor is it a specific method that stands on its own. It rather offers a way to broaden the understanding of problematic situations in order to gain new insights and create room for improvements that last. ST is a methodological framework, not a method as such. It is open to methods that adhere to the methodological principles discussed in this book. The methods that we use in our daily practice are discussed extensively.

ST, and therefore this book as well, is all about learning. Learning about the problematic situation at hand and about how to realize widely supported change. But also learning about ST itself. It is an ongoing process of joint learning, explication, collaboration and validation with stakeholders involved – a process of a participatory, interdisciplinary, iterative and reflexive nature. Every situation encountered, offers new insights, new expertise. When reflecting upon these insights together, we learn more and more about how to reach sustainable change. And this expertise will also be used to further develop ST. Just as our society, ST is not static and has to move as well.

Reading guide

This book should not be read from cover to cover. It contains different sections. Some are mostly practical, others mostly theoretical. It can be read back and forth. This introduction has set out the context from which ST has derived. When diving into Social Theory for the first time it is advised to now move on to the Summary and the Principles and Ground Rules chapters describing the main principles and concepts behind ST. All other chapters derive from and build on these principles and concepts. Those that like to learn from practice are advised to continue reading the Facilitator Guide. This chapter offers practical tools and examples. Even without reading the more detailed chapter on the ST or the chapter on the theoretical foundation, this chapter should enable the reader to put ST to practice. In Social Theory of a Sustainable, Collaborative Learning Society a more detailed chapter is offered on ST and its accompanying Social Innovation (SI) process. The chapter Foundation delves deep into the theoretical foundation of ST. This chapter is not one that is easily digested, but it will give new insights and a more profound understanding of ST to those that are interested into a more theoretical background. The Second Ring chapter, in addition to the Facilitators Guide brings across several other methods/theories/concepts that, in light of ST, could be of use. This chapter is one that will be added to over time, finding more methods that help putting ST to practice.

This book is not one to read once and expect all information to stick. Reading it over time will help gain new insights. It can be compared to reading a whodunnit. When reading a book like that, several clues will be given about who committed the crime throughout the book. Most of these clues will not be noticed. Only after the plot has been revealed, and when re-reading the book, all clues will become visible and fall into place.

- Lees hiervoor:

- Lees hierna: