MediaWiki:LC 00819/en

Social innovation principles ppt (English)

Social innovation – a short introduction

A matter of identity and culture: who we are (or want to be) and what we do (or want to do)

Social innovation can be seen in many ways. Our point of view is that social innovation is a process that is used to tackle wicked problems. Wicked problems are issues in which various parties have differing and opposing interests and points of view, which are not easily united. What is a problem for one party, means something else entirely to another party. There are many examples of this, such as climate change, geopolitical conflicts and the increasing gap between the poor and the rich. Wicked problems are often intertwined with other wicked problems. All this means that it is not easy to understand an issue or find solutions for it that are acceptable for all parties. It requires a carefully thought out process of Social Innovation (SI) that brings parties together to take joint steps forward.

The SI process described here gives a central role to the societal challenge. That means that it surpasses individual parties. The SI process aims at obtaining arguably desirable and culturally feasible societal changes. The solutions should not only be rationally and technically feasible, but they also have to fit into a society’s culture. A culture is not a static condition; rather, it is something that is constantly in motion through mutual influencing. Through dialogue for example. In essence, the SI process focusses on identity and culture. It is a process to decide who we want to be and what we will do.

Key notions of social innovation are mutual understanding and shared meaning. The SI process starts with creating mutual understanding: recognizing and acknowledging each other’s worldviews, who we are and what we do. The next step is explicating shared meaning, which aims at taking solution-oriented steps that fit in with the culture’s and individual’s identities and serves a higher purpose at the same time. Recognizing and acknowledging each other’s worldviews is essential in this, because through dialogue, several aspects of the challenge are shared which may lead to a broader understanding of said challenge. This creates room for change.

The process of social innovation

The SI process is based on the following three principles, one axiom and two injunctions:

- Axiom: we got to move;

- Injunction 1: Create room for change;

- Injunction 2: Determine the right direction.

We got to move

People are adaptive beings. They use their senses to explore their surroundings and, if necessary, react. Movement is in our blood, especially in case of immediate danger. We are faced with serious challenges (wicked problems). Not yet everyone sees or feels the urgency, but despite that, taking proactive measures is imperative. Doing nothing is not an option. It is not just necessary to face the current wicked problems, in the future we will have to face new wicked problems, which may or may not be of our own making. In short: it is a given that we are in motion as an inherent condition of being human, or that we should be moving in case of urgent, existential threats. In any case: we got to move!

Create room for change

We got to move, but without room, movement is impossible. Room for change can be created by recognizing and acknowledging each other’s worldviews. When doing so, you have to look beyond the surface and not just focus on how people or organizations act, but instead look at deeper motivations, i.e., a person’s identity or an organization's culture.

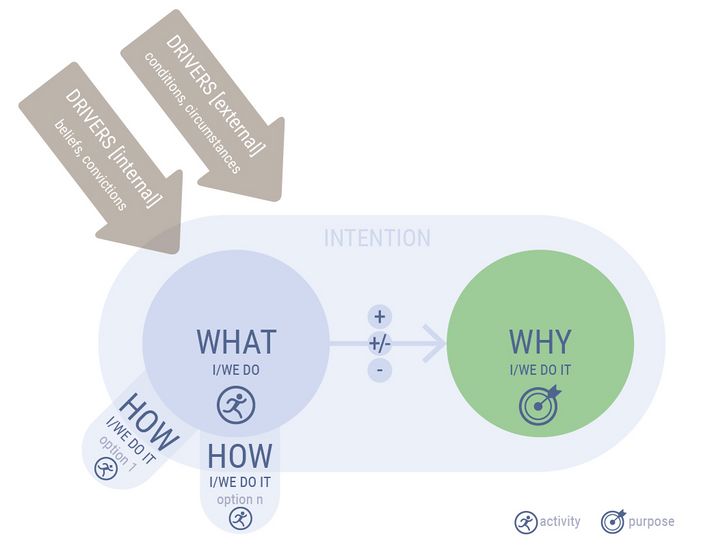

The model below shows how an individual’s or organization's worldview is interpreted. The model is based on the Soft Systems Methodology PQR formula (P-what, Q-how and R-why). A strict distinction is made between the intentions (motivation, driver: the what-why) and the manifestations (tangible, observable: the how). Intentions are based on convictions and assumptions one has, regarding the world. The intentions, convictions and assumptions together form an individual’s or organization's worldview. They not only determine the way one regards the world, but is even felt by individuals or organizations to be their reason for existence.

To save us all some time (and repetitions) the term ‘individual or organization’ will not be used in the remaining text and the all-encompassing term ‘party’ is introduced from here on in, knowing that anything that is said about a party, applies to both individuals and organizations. In case of an organization, it may be better to speak about a mission (what), vision (why) and strategy (how).

Oftentimes, there are various options for shaping intentions, i.e., several concrete manifestations (courses of action – the hows). A choice between courses of action is made based on or driven by the then current internal and external conditions.

By filling in the schematic above for various parties, an inventory of possibilities for change is made. For example, an organization can choose a different course of action which validates its own reason for existence and which also benefits the entire challenge because of mutual facilitation. Put simply: help each other out a bit and this way also do something that serves the common good (see also the following section).

You gain insight in underlying motivations by using guided conversation (see Facilitator Guide and Research Philosophy and Process). In these conversations you seek out convictions and assumptions by means of concrete activities.

In the ST of a sustainable, collaborative learning society social theory of a sustainable, collaborative learning society this model is worked out further, with, as a basis, the development of parties through self-reflection and interaction with other parties.

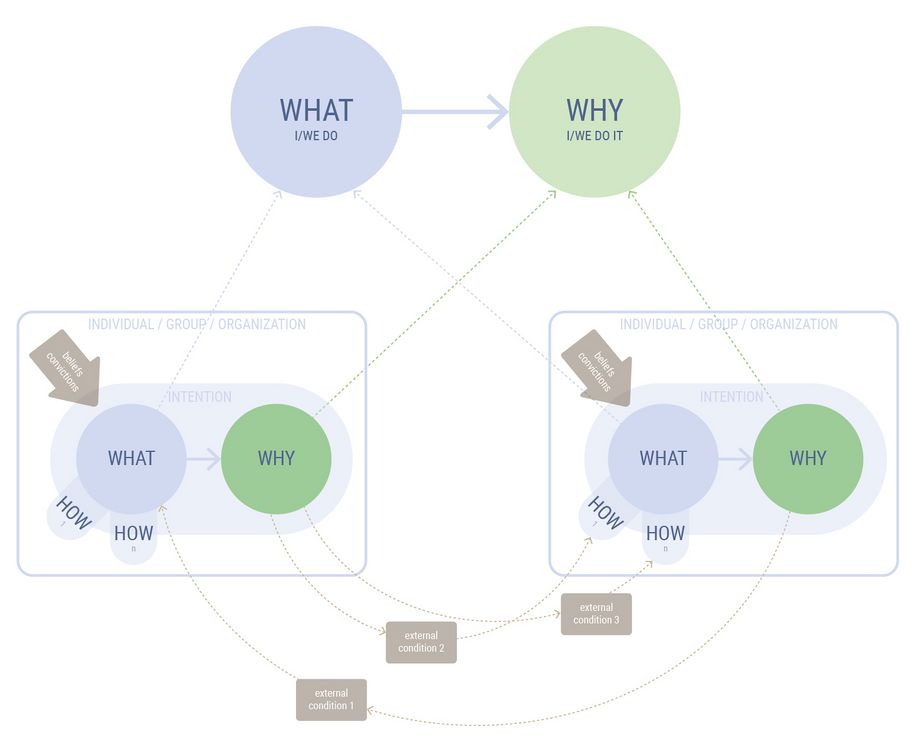

Just creating room for movement is not enough. We will also have to jointly determine what the right direction is. The aim in this assignment is finding common motivation for the challenge. With the worldviews (what-why and how) as a basis, dialogue (co-creation sessions, serve this purpose, for instance, see Facilitator Guide) is used to reconstruct a mutual motivation (what-why), as depicted in the illustration below. This mutual motivation will, generally speaking, be more abstract in nature than individual parties’ motives and encompasses shared values. It forms the basis for finding options for solutions.

To illustrate this somewhat abstract description of the search, we will use the current healthcare situation as an example. When you examine this situation closely, you see that a large number of parties is involved with a client’s health, amongst them the GP, hospital, homecare, dentist and paramedics. All these parties have their own reasons for existence, which is partly aimed at providing good care, but also at the continuation of their own organization. In the all-encompassing situation of healthcare, the patient’s well-being takes center-stage, or at least, that is how things should be. The all-encompassing reason for existence and shared meaning could, then, be that clients, through awareness, reach and maintain an acceptable level of living, supplemented by norms and values such as positive healthcare and self-controlled care where possible.

Shared meaning is often implicitly present in situations. The main issue is to make implicit shared meaning explicit. This is, in fact, a reconstruction process to oust the things that are left unsaid.

In theory, each individual party’s reason for existence (what-why) should be traceable to the common reasons for existence. In practice, this will, mostly, not be the case entirely. To bring about change in the all-encompassing situation, parties will have to change. There are various ways to do so (see Exploring Change):

- Better facilitation through other parties in order to be able to do things right. In case of care, for instance, sharing information can help establish a holistic view of a client’s condition, which means that an individual party can use a more targeted approach.

- Choosing a different work method (how) that fits in better with the whole, but possibly also leads to a better facilitation of other parties. I.e., in care, one party can partially take over another party’s work to prevent doing the job twice.

- Assuming a different reason for existence (what-why). If an organization’s reason for existence cannot or can hardly be linked to the reason for existence of the entire situation, then that organization should or must opt for another reason for existence. And if that reason for existence cannot be found, then it can be concluded that the organization in question no longer has a reason to exist, at least not within the all-encompassing situation. I.e., an organization that does not endorse the values and norms of positive health, can hardly be expected to contribute constructively to the whole.

Ground Rules

The SI process can only succeed if parties are willing to take steps collectively. This can only be achieved if everyone abides by the following two ground rules:

- Rule 1: co-dependency implies care responsibility.

- Rule 2: Diversity in opinions (worldviews) is a basic and essential right for achieving sustainable changes.

No party stands on its own. Everyone depends on others and therefore has care responsibility to others (see Ethics of Care). Care is not used here in the physical sense of the word, but rather in the sense of attention, kindness, concern, intervening, etc. The consequence of this rule is that parties go beyond their own boundaries and address the needs of other parties. And looking at it the other way round, each party also has to make clear in which ways others can contribute. In the current climate where the focus lies on self-actualization and economic growth (often at the expense of others), going beyond one’s own boundaries is not a given. There is, however, a reversal at hand in which care responsibility is used as a leading principle, but this is far from being commonplace yet.

In a democracy, everyone has a right to have their own worldviews and, is, within boundaries, also allowed to act in accordance with said worldviews. This does, however, not mean that everyone recognizes, let alone acknowledges other party’s worldviews. For the creation of room for change, the principle of recognition and acknowledgement of worldviews is essential. Furthermore, parties that hardly have a voice, such as nature or future generations, should also have a voice in this.

In practice, not all parties will genuinely endorse the two ground rules. The consequence of this is that the possibilities for change will be limited. This does not mean that the SI process is limited, rather it is an indication of the (inherent) limitations of parties that require attention. Bringing about progress in complex social issues, is not an easy thing and it requires a setting in which social innovation takes place. The SI process takes time, and the timing has to be right.

Sustainable Changes that Last

The SI process of mutual understanding (injunction 1) and shared meaning (injunction 2) gives insight in the feasibility of joint change. Insight in itself is not a guarantee for success. In order to achieve desired changes, all parties will have to move. What if one or more parties drag their heels and the facto veto change? Or put differently, who or what denies a party the right to only act in their own interest? Underneath all this, there is a deeper question that deals with the difference between validation – are we doing things right– and verification – are we jointly doing the right thing? What are these ‘right things’ and who decides what they are?

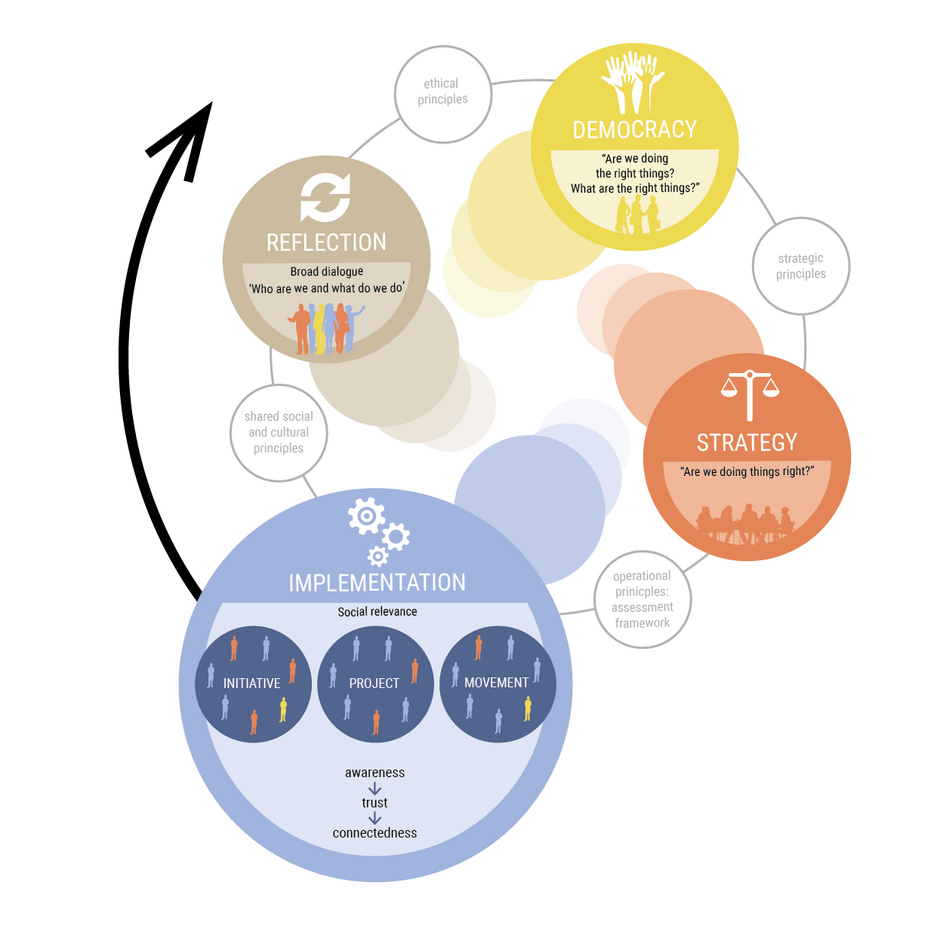

The ‘circles graph’ answers the questions posed above (see Social Innovation Process). The large blue implementation circle represents the above described SI (implementation) process of mutual understanding and shared meaning. The implementation process falls within the boundaries set by the operational assessment framework that is established in a democratic and strategic process. These two last processes in their turn take place within the assessment frameworks of a reflection process (with broad dialogue) fed by the lessons learned from one or more implementation processes. From the lessons learned follows a value and norm system that in its turn leads to an adjusted assessment framework for implementation processes. The whole forms top-down and bottom-up processes of, respectively, verification (do things right) and validation (jointly do the right thing) based on practice (lessons learned from the implementation processes) and broadly supported (reflection and broad dialogue).

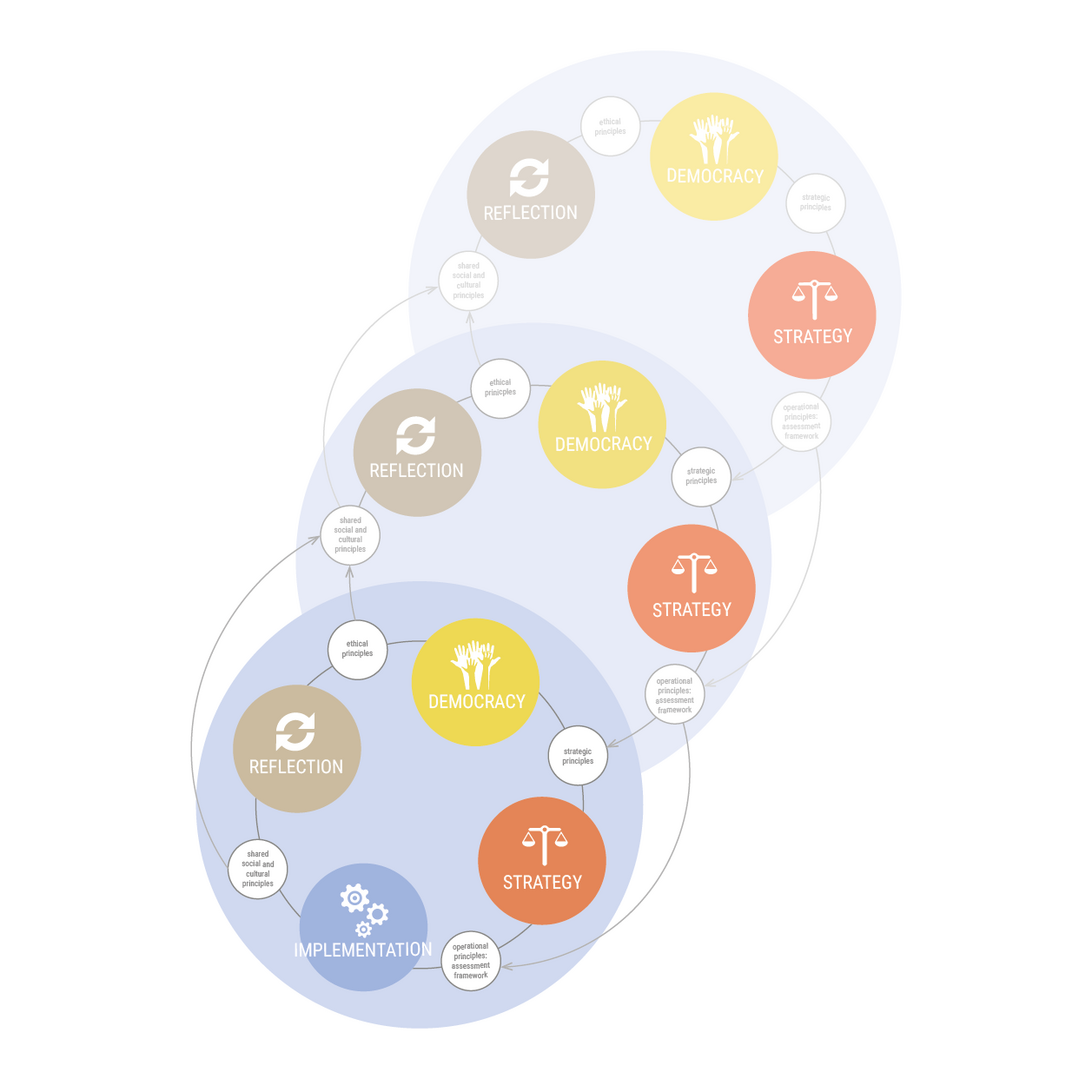

The figure below shows how several of these processes can be connected with each other on several levels of abstraction (see Beyond Local Initiatives). For example: the worldwide climate deals can be linked with national and regional initiatives. But at the same time, lessons learned from local initiatives shape the policies that should be implemented on regional, national and global level.

This way, the small is connected with the large, and vice versa. The linking surfaces are based on identity and culture: who we are (or want to be) and what we do (or will do).